During the holidays, most of our clients rested taking advantage of the holiday season. Whereas, I had more time to broaden my horizons. Thanks to the kindness of my teammates, I learned a lot about automation and more. My friend Rafał agreed to share his knowledge about the LEAN SIX SIGMA philosophy with me.

The Expert’s eye:

The people I often talk to ask me if a given process can be automated? To some extent controversially, I always answer yes. Nevertheless, I always add that the more important question is whether the process can be automated in its current form. At this point, the situation is usually already complicated and it appears that automation is only the next step to be taken on the way to a specific destination, but certainly not the first one.

It is said that the only constant in life is change.

The same applies to processes that are constantly evolving through changes in the environment in which they work. These can be legal, technological, internal structure or customer profile changes. For example: working with paper documents is giving way to their digital counterparts, which has forced the implementation of digital signature tools.

This also leads to the deployment of a methodology to address the implementation of Continuous Improvement. One of them is the LEAN SIX SIGMA, which is a combination of the Lean and the Six Sigma concepts which tries to implement and combine the best solutions from both approaches. It is based on several key issues.

Genichi Genbutsu – freely translated as “go and see”. The essence of this approach is that managers should not only spend time behind the desk, but also go and see the causes of a problem situation at its source, i.e. where the specific product is being manufactured. The point is that, in order to solve specific problems, it is first necessary to thoroughly familiarise oneself with each stage of the process, carry out an analysis and draw conclusions. For business process automation this means that managers and directors should also be familiar with the processes performed by their subordinates. This makes it easier for them to identify which processes should be automated first from the perspective of the company strategy. Decisions should be based on the following steps:

- Set the goal

- Select the area

- Visualise the process

- Observe and ask questions

- Review the observations

- Identify the differences between the actual situation and the desired situation

- Present the results

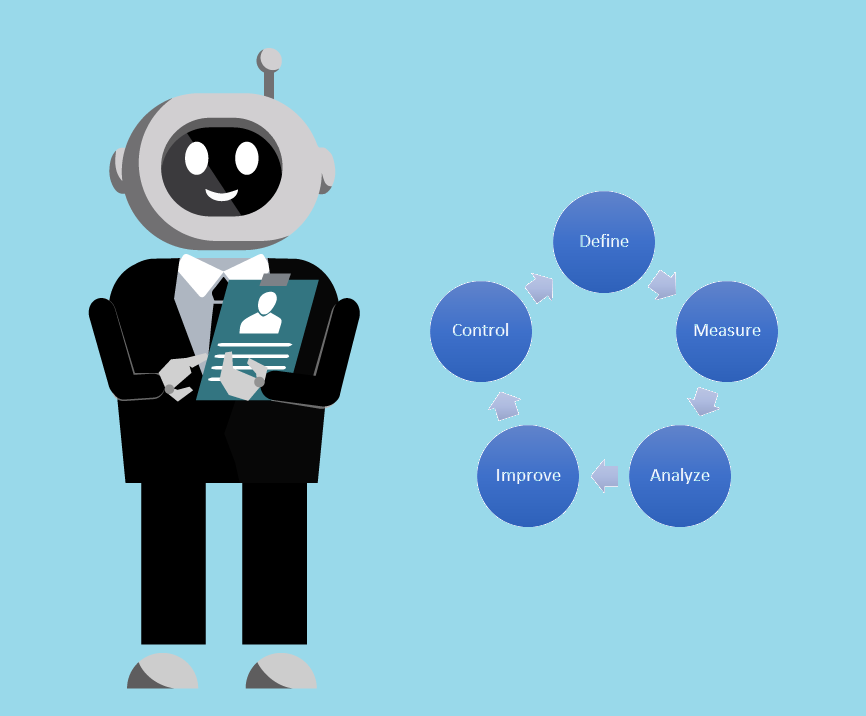

The sequence of these successive events is very similar to the next Lean Six Sigma issue, which is the DMAIC cycle consisting of five phases.

DEFINE

The Define phase allows you to determine exactly what the problem is and what is necessary to solve it. The goal set like this should be SMART, i.e. specific (S), measurable (M), achievable (A), relevant (R), and time-based (T).

MEASURE

This allows you to move to the next phase, that is Measure, where we describe how to make observations, and then make appropriate calculations to determine the current process efficiency.

ANALYZE

This leads directly to the next phase – Analyse.

IMROVE

At this stage, we already have the basic data available to make a decision, which allows us to implement the necessary changes in the Improve phase. The devised solution should be tested, checked, and finally implemented. To do this, you can use the PDCA cycle and the FMEA.

CONTROL

The last phase is Control, which is designed to verify the assumptions which have been made and to determine whether the specific problem has been solved.

The already mentioned PDCA, known as the Deming Cycle, is based on dividing the implementation of an improvement into four stages:

- Plan – placing the main focus on what is not working properly

- Do – implementing changes as a test

- Check – reviewing the results to see if the test has passed

- Act – implementation into production

Methodology circularity is characteristic here, since the end of phase Act should result in starting phase Plan again. However, if the experiment is unsuccessful, you should skip the implementation into production phase and move back to preparing a new plan – until the problem is solved.

How can the FMEA be implemented in all of these? FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) is an analysis of the types and effects of possible errors and is aimed at taking preventive actions to prevent the effects of defects that may occur at both the design and manufacturing stages. The main assumption is that approx. 75% of errors occur in the production preparation phase. On the other hand, they are detected only at the production phase and during the operation (approx. 80% of errors). How does it work? In the first stage, we first need to set our goal, gather the team, decide what we are going to analyse, break the process down into its constituent parts, and finally collect the data. They in turn will serve us at the time of both the qualitative and quantitative analysis. The final step is to plan corrective actions, implement them, and observe.

All the elements which I have written about can be implemented very well both in the deployment of further automations and in the optimisation of already existing processes. Before a programmer begins to work, he or she has to go through the Genichi Genbutsu procedure together with the analyst to get a good understanding of the process to be automated. Then they create a master work plan which is very similar to the way the DMAIC cycle works. The programming itself takes the form of: Plan => Program => Test => Deploy, which is deceptively similar to the PDCA methodology. At the same time, the programmer together with the SME and the analyst prepares the list of potential errors and determine how to handle them in accordance with the FMEA method. Perhaps not everything runs by the book or contains standard documentation, but the hard core of these methods is always the same.